Our AFA Annual Meeting (AFAAM) in 2010 was held in Phoenix, Arizona. To be honest, it was the first time I was afraid to attend the Annual Meeting because Arizona had recently passed AZ SB 1070, which allowed law enforcement to racially profile and stop any individual who “may look” undocumented. It was the first time I can remember genuinely being concerned for my safety since immigrating to the United States.

At that time, I was serving as president of the National Multicultural Greek Council (NMGC). I recall my National Association of Latino Fraternal Organizations (NALFO), National Pan-Hellenic Council, Inc. (NPHC), and National APIDA Panhellenic Association (NAPA) colleagues and I urging the association to consider changing the conference location. Citing conference site investment costs, the request became a moot point. That year at the Annual Meeting, my friend and colleague Monica L. Miranda was being installed as the association’s first president of color. She was also the first member of a Culturally Based Fraternal Organization (CBFO) and Latina to lead the association. The fact that it was in Phoenix, amid the passage of SB 1070, meant many of our CBFO association members flying in to celebrate the momentous occasion could face hostility from local law enforcement.

I debated going, given that I am a Brown-skinned human. I armed myself with courage and refused to be silenced in celebrating my interfraternal sister’s accomplishment. I went to the 2010 Annual Meeting, but I can tell you — the moments outside the Annual Meeting’s confines were nerve-wracking.

On May 9, 2011, I was at Bradford Woods, Indiana University’s campsite in Martinsville, Indiana. It was Day One of LeaderShape, and I was serving as a family cluster facilitator for Indiana University’s session. All our students had arrived for check-in by 5:00 p.m. — all but two of my Multicultural Greek Council (MCGC) executive board members, Omar and Eric Gama. I became concerned because they knew how important it was to attend the retreat. They would not simply miss it.

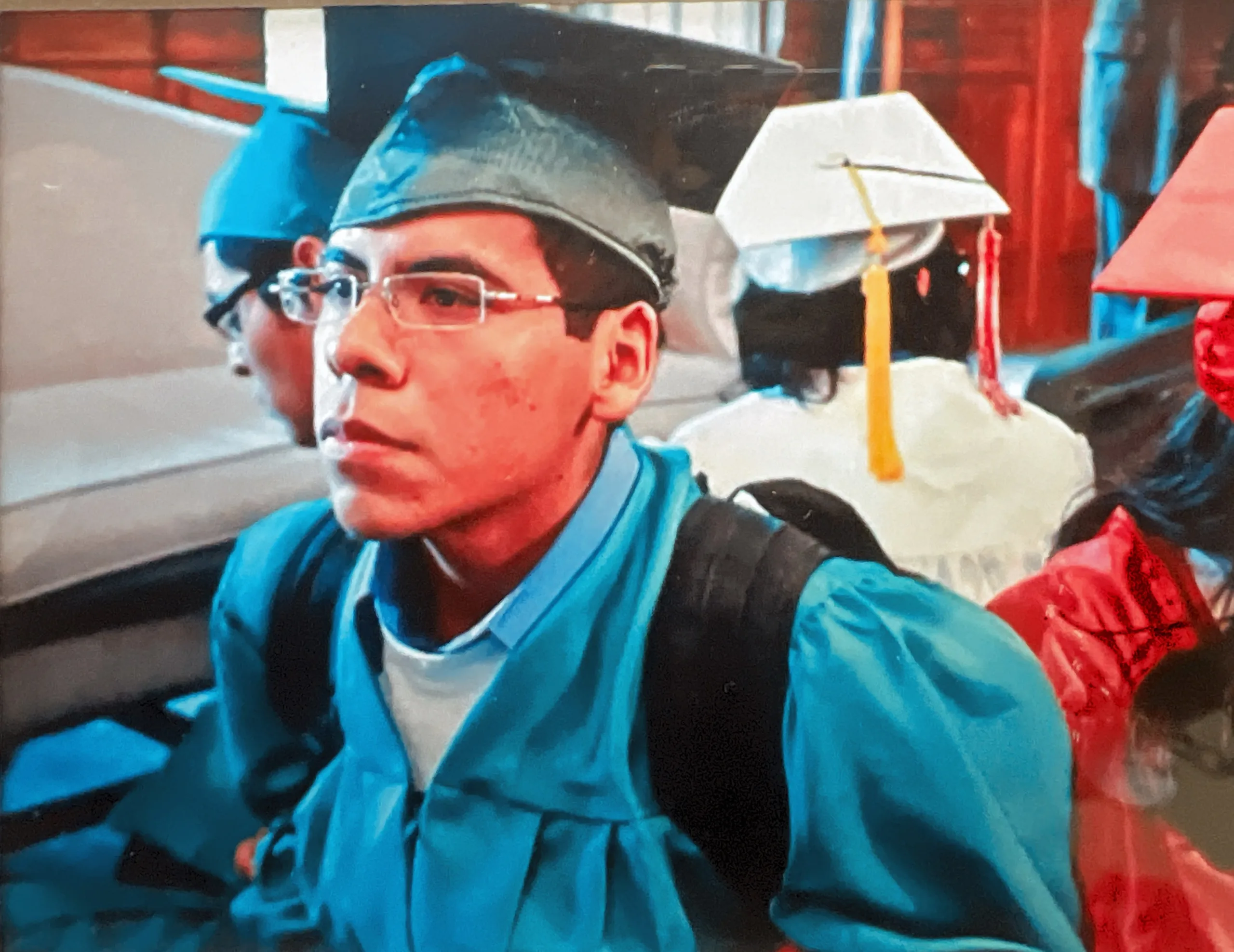

When I couldn’t reach them by phone, I asked other MCGC members if they knew where the Gama twins were. Responses began to come in — they had been arrested and were being held in an Indianapolis jail. Earlier that day, they had been arrested for refusing to leave the statehouse while requesting an audience with then-Governor Mitch Daniels. House Bill 1402/Senate Bill 590 would prohibit them from paying in-state tuition as undocumented immigrants. They became known as part of the Indiana 6 — Dreamers who emerged from the shadows to advocate for themselves and their peers to continue their education as Indiana residents.

My heart sank. Omar and Eric were undocumented immigrants. I did not know, much like everyone else, their immigration story. Similarly, no one knew my story either. They risked their lives and their freedom to advocate for equity — a fair ask of the state’s governor: not to sign the bill into law. How? How are they undocumented? They are in Lambda Upsilon Lambda/La Unidad Latina Fraternity, Inc. They are known student leaders in Bloomington. They stepped out of the shadows and put their safety at risk. How did they have the agency to be so bold, so brave, when I (a naturalized United States citizen) was not?

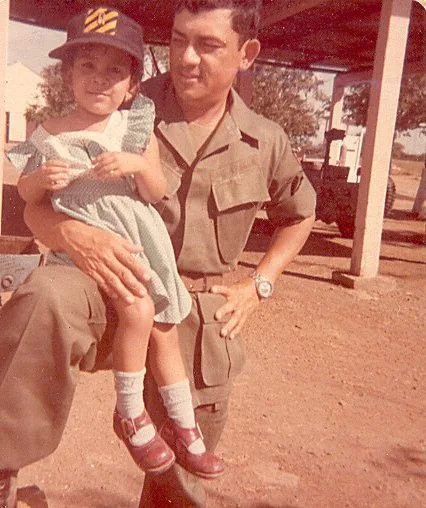

I was born in Managua, Nicaragua, into an extremely involved military family with a legacy spanning generations. My father, Cristobal Medrano Castañeda, an infantry captain, died a hero. On June 23, 1979, he was killed in action during a military confrontation with the Sandinista Regime. I was almost three years old when I saw my father for the last time.

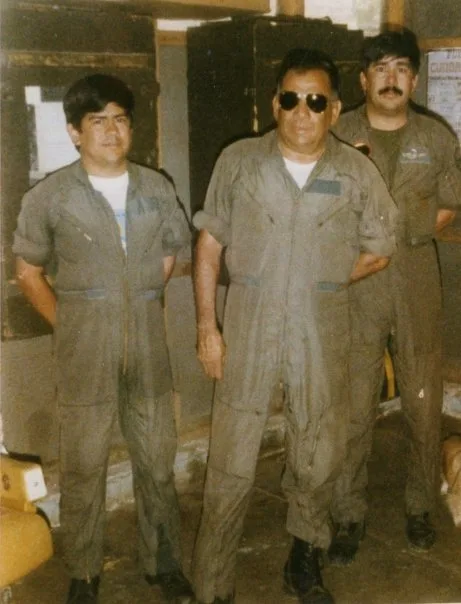

My mother, J. Violeta Gómez Avilés, although a civilian, worked for the Nicaraguan Military Academy. My uncle, Juan M. Gómez Avilés (my mother’s brother), was a fighter pilot and a colonel in the Nicaraguan Air Force. My cousins also followed suit, becoming fighter pilots and lieutenants in the Air Force.

At the climax of the Sandinista Revolution, my mom and I became military targets — potential hostages to be used as bargaining chips. I vividly recall one night: my mom and I were in our living room when a hail of machine gun bullets shot through our windows, narrowly missing our heads. My uncle Juan told my mom to go to Guatemala to wait out the war. He advised my mom that the Contra Revolutionary Movement was gaining momentum, and it seemed the conflict would soon be resolved because now the United States was involved.

We headed to Guatemala while my other cousins were granted political asylum in the United States. Things quickly deteriorated in Guatemala as militia confrontations erupted with the government and communist guerrillas. President Reagan was offering political asylum to Nicaraguans persecuted by the Sandinista government. My mom decided we had paid enough visits to the U.S. Embassy — it was time to go to the United States, where we could be safe.

We arrived in Miami, Florida, on May 30, 1982. My mom and I received political refugee status shortly after arriving with I-94s, social security numbers, and indefinite work permits. That remained my status until September 21, 1999, when a federal judge granted my mom and me permanent resident status.

I was finally able to finish my college education! I enrolled at the University of Florida for the spring 1999 semester. At Florida, I joined Gamma Eta Sorority, Inc., Alpha Chapter. Gamma Eta had just been incorporated, and I came in as part of the first new member class in fall 1999. Since then, I have worked tirelessly for something greater than myself, fulfilling our founders’ dream of becoming a national sorority that espoused Leadership, Unity, Sisterhood, Strength, Service, Scholarship, and Diversity.

Working for something greater than myself was exponentially influenced by my fraternity and sorority work coordinating logistics for the Interfraternity Institute (IFI) at Indiana University with Steve Veldkamp and Jeremiah Shinn. The Call for Values Congruence became the vision I continue to strive for, by embracing a “healthy disregard for the impossible,” as Mike McRee taught me during my undergraduate years at LeaderShape. I continue to have faith that values congruence can be attained within collegiate Greek-letter fraternal organizations. This call to action continues to be relevant to me as it shapes the framework for accountability within every fraternity/sorority community I lead.

During my time in Indiana, I learned more about myself. I learned about the privilege I hold as a U.S. citizen — May 14, 2008, after waiting 26 years, my mom and I became U.S. citizens — and my responsibility to advocate for those who do not have a voice, like Eric and Omar Gama at the time. I also learned the power of counter-narratives (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001) — the ability for historically marginalized people to tell their stories. During my doctoral work, after several conversations with Steve about values congruence, I realized the work of all our founding mothers and fathers was a manifestation of their agency to go against the status quo and write their own counter-narrative. Like Eric and Omar were doing as student leaders within my MCGC, they were going against the status quo with a (somewhat) healthy disregard for the impossible. They were the “helpers” in this case, using their fraternal capital to advocate for those who did not have it. Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc. came through for them, and many other historically Latino/a organizations also advocated for undocumented members of their organizations.

As a part-time history scholar under Dr. Andrea Walton’s tutelage, I learned to work with primary documents. I began visiting university archives to examine original materials that told the stories of our fraternal organizations. With the help of my interfraternal sister Fran DeSimone Becque and Ellen Swain at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Student Life and Culture Archives, I have dug deeper into archival research, uncovering primary documents and artifacts that have documented the resiliency of so many fraternity and sorority founders. It has been enlightening to teach our fraternity and sorority students this historical perspective.

When Phi Beta Kappa was established on December 5, 1776, at the College of William and Mary, its founders met in secret to discuss progressive ideas — typical of the Enlightenment Era — which were not in line with the colonial college curriculum focused on creationism (Tobenson, 2009). Women’s fraternities evolved post-Civil War to provide safe and supportive academic and social spaces for women (Shaw Martin, 1931), despite the claims of scholars like Harvard professor Dr. Edward H. Clarke (1873), who argued in Sex in Education; or, A Fair Chance for Girls that rigorous academic work would cause women to become infertile.

The first collegiate culturally-based fraternal organization emerged with Zeta Beta Tau in 1898, the first historically Jewish fraternity, created to support Jewish students who were immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe (Sanua, 2003). The founding of Alpha Phi Alpha in 1906 — the first historically Black fraternity — defied academic and social barriers at predominantly white institutions, advocating for civil rights and women’s suffrage during the era of Jim Crow (Ross, 2000).

The establishment of Rho Psi in 1916, the first Chinese American fraternity at Cornell, created a space for Asian American collegians who had faced the injustices of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The founding of Phi Iota Alpha in 1931 marked the beginning of Latin American international students organizing for academic success and political discourse on Pan-Americanism. “The mission of Phi Iota Alpha operates under the ideology of Pan-Americanism, which is the ‘unification of Latin American nations and all Latin American people’” (Muñoz & Guardia, 2009, p. 108).

As more Latinx students immigrated to the U.S. due to the Cold War, the establishment of Lambda Theta Phi and Lambda Theta Alpha in 1975 served as catalysts for using brotherhood and sisterhood as tools to preserve Latino culture and advocate for their needs on college campuses. “The concept of embracing the ideals of Latino unity, cultural awareness, brotherhood, community service, and Latino empowerment… must be accredited to Lambda Theta Phi… [to] achieve equal representation and justice” (Peña, 2001, p. 3).

Fast forward to the present-day United States. I am often disillusioned by what has happened to our progress since 1776, both politically and fraternally. I grieve what I once thought was a shared American value in equity and social justice. I mourn the loss of humanity in some. Like identity development, grief follows five stages, according to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. For me, this process is not linear but cyclical. Each time a new executive order is signed, or unjust legislation is passed, and court orders are disregarded, the cycle repeats.

As a student affairs professional — specifically, a fraternity and sorority advisor — I wear my heart on my sleeve. Some say vulnerability is dangerous, but I believe it shows humanity. My hope in humanity, the belief that we are innately good, is what keeps me going, even in the face of today’s gaslighting and propaganda. That, and my unwavering faith in Jesus Christ, keep me from falling into despair. Like I said, my grief is cyclical. As the current generation of students come to me to voice their concerns, their hopelessness and disbelief in the situation, I always must dig deep to help them see the light at the end of the tunnel, even though I am living through their same emotions. As the old proverb says, “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” I pour into them constantly. Concurrently, there are times when my cup runs dry, and they pour into me. Literally, one of my Panhellenic women came into my office after the 2024 election with a Starbucks Lemonade Refresher because she heard my “cup had run dry.” I rejoiced at her astute kindness to make light of an otherwise devastating moment for me (and her). I focus on moments like this to help me keep going. She was my helper.

I have a shirt that reads: “I am my ancestors’ wildest dreams.” I also think of my mother’s resilience and my family’s survival — not just through adversity in the U.S., but through a literal war. As an immigrant, a member of the working class, raised in a single-parent household, and an at-risk youth, I carry that strength. I keep going. I focus on those who have helped us.

I think of the resilience of our fraternity and sorority founders and the spirit of survival within their historical contexts. I am in awe of their courage. I know that always having courage can be exhausting. My whole life has involved courage, and it has been my counter-narrative. I grow tired. I grow weary. My heart sinks — then I remember the resilience of our founders, my students, colleagues, and friends that serve as my constant sounding boards. Also, my professors — who, thanks to academic freedom, were able to point out the narratives and were able to show me how to document and tell counternarratives. It is a breath of fresh air because we are all helpers.

I observe our persistence, kindness, and, most importantly, the congruence between the values we espouse and the values we live. That — and my faith in humanity — is what keeps me going. Good always prevails. Light always defeats darkness.

When I was growing up, I recall Mr. Rogers saying, “When I was a boy and would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You’ll always find people who are helping.’” I’m grateful for my village that overflows with helpers. They keep me going. And much like Orphan Annie sang, “The sun will come out tomorrow.” And that, my friends, is something we can always count on. So just go. And be brave.

References

Munoz, S.M. and Guardia, J.R. (2009). “Nuestra historia y futuro (Our history and future): Latino/a fraternities and sororities.” In Torbenson, C.L. & Parks, G.S. (Eds). Brothers and sisters: Diversity om fraternities and sororities, pp. 104-132. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press: Teaneck, NJ.

Pena, J. (2001). Latino by birth, Lambda by choice: The history of Lambda Theta Phi Latin Fraternity, Inc., Second Ed. Vantage Press: New York, NY.

Ross, Jr, L.C. (2000). Divine Nine: The History of African American Fraternities and Sororities. Kensington Publishing Corp: New York.

Sanua. M.R. (2003). Going Greek: Jewish college fraternities in the United States, 1895-1945. Wayne State University Press: Detroit, MI.

Shaw Martin, I. (1931). The Sorority Handbook: Eleventh Edition. Ida Shaw Martin, Publisher: Boston, MA.Torbenson, C.L. (2009).

“From the beginnings: A history of college fraternities and sororities.” In Torbenson, C.L. & Parks, G.S. (Eds). Brothers and sisters: Diversity in fraternities and sororities, pp. 15-45. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press: Teaneck, NJ.

About the Author

Christianne I. Medrano Graham currently serves as the director for Sorority and Fraternity Life at Ohio University. She is President Emerita of the National Multicultural Greek Council and Gamma Eta Sorority, Inc. She earned her Master’s in Student Personnel in Higher Education and her Bachelor’s in Arts in English and Secondary Education from the University of Florida. She has also loved serving in numerous volunteer roles within other international fraternities and sororities and professional associations. She lives in Athens, Ohio, with her husband, Adrian, and her fur babies, Roxy and Sofia.