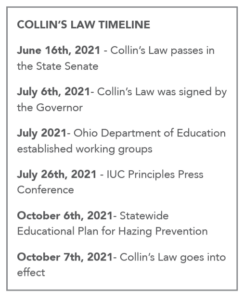

Two hazing deaths in Ohio between 2018 and 2021 propelled legislators to pass Ohio’s anti-hazing law, Senate Bill 126 “Collin’s Law,” which went into effect in October 2021. The law and additional requirements for public schools created a shift in hazing education training, reporting procedures, and policies. Impacting more than just fraternal organizations, sorority and fraternity (SFL) staff in Ohio have worked collaboratively with other departments and stakeholders to roll out their compliance plan while elevating prevention efforts.

Two hazing deaths in Ohio between 2018 and 2021 propelled legislators to pass Ohio’s anti-hazing law, Senate Bill 126 “Collin’s Law,” which went into effect in October 2021. The law and additional requirements for public schools created a shift in hazing education training, reporting procedures, and policies. Impacting more than just fraternal organizations, sorority and fraternity (SFL) staff in Ohio have worked collaboratively with other departments and stakeholders to roll out their compliance plan while elevating prevention efforts.

Currently, 44 states in the United States have anti-hazing laws[1]. Anti-hazing laws fall into one of three categories (see Figure 1) and approximately a dozen states have laws that consider hazing a felony. Many of these laws incorporate concepts from the Anti-Hazing Coalition’s model legislation[2], a result of legislation and family lobbying efforts as new anti-hazing laws have been proposed. These concepts include mandatory reporting, maintaining a transparency report on the university’s webpage, and providing anti-hazing education to campus community members and volunteers. These three requirements are all found in Collin’s Law.

When Collin’s Law passed, many colleges and universities in Ohio looked to SFL staff to serve as hazing prevention content experts. Sorority and fraternity practitioners navigated infrastructure and processes, sought support and resources, and relied on colleagues across the state to formulate best practices. Action items continued to shift and change as individual universities and the Inter-university Council of Ohio (IUC)[3] launched policies and anti-hazing principles. The additional variables meant staff members and working groups must navigate multiple priorities and competing interests collaboratively.

Summer 2023 will mark two years since the IUC principles were released and Collin’s Law was passed. As practitioners reflect on the enactment of Collin’s Law and the implementation phase, members of the Ohio SFL coalition want to offer strategies to help other practitioners across disciplines who are tasked with implementing new legislation.

- Your Role as a Sorority and Fraternity Practitioner: SFL is mentioned in many pieces of legislation and state/local anti-hazing initiatives. While hazing does not isolate itself to just sororities and fraternities, these groups remain a priority area for prevention education. As noted earlier, as laws are passed, SFL professionals are called upon to help navigate legal requirements and develop campus-wide education. If SFL professionals find themselves at this table, they must be centered in a place of innovation and advocacy. Sometimes they may find themselves advocating for the fraternal experience; other times, they may advocate for widespread education. Many campus partners might be new to conversations about hazing prevention. Therefore, they may rely on assumptions while engaging in this prevention work. SFL practitioners need to ensure that when decisions are made, there is parity across all student organizations and groups.The implementation of anti-hazing laws has provided many campuses with consistent baseline expectations and education on identifying hazing behaviors and how to report them as an individual to both campus and local law enforcement. Practitioners need to implement intentional education and requirements that support the development of student groups on campus.There is an opportunity for anti-hazing efforts to aid in creating a positive group environment for new and active members. Therefore, it may fall to the SFL practitioner to challenge partners to think past a check box requirement to create transformative opportunities for the students they serve.One way SFL practitioners can be transformative is by grounding this work in cultural competency. Operationalizing and defining diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) will aid in understanding structures that influence hazing behaviors. Additionally, prioritizing DEI training is important to establish relationships with groups and engage students effectively. For example, when considering SFL anti-hazing efforts, utilizing a blanket approach is not an effective or equitable option. Each council and chapter operate differently and have different social norms around the new member process. Staff members must critically examine laws, best practices, and strategies with cultural competency and intersectionality. Often best practices and the experience of legislators developing anti-hazing laws exclude dynamics or experiences of identity(ies) and groups outside of the dominant narratives. Here, professionals can advocate if their campuses are asked for feedback from government affairs and push for culturally relevant education methods on campus.

- University Priority Areas: Anti-Hazing laws require a variety of areas around the institution to invest more time in prevention work. As a result, universities are making more substantial commitments to eradicating hazing on campuses, so it becomes vital to consider areas outside of SFL to start to shift campus culture. The media’s focus on fraternity hazing can cause other group’s behaviors to be overlooked. However, Allan et al. (2018) determined that hazing is likely to occur in athletics, fraternities and sororities, club sports, and band and performing arts organizations.Hazing activities are different depending on the group, identities, and campus. What is relevant for a fraternity or sorority may not relate to a club sports team. As teams begin to build a strategic plan around law implementation, creating a list of priority areas is important. Some areas are easy to determine. For example, staff already engaged in prevention work, groups who have had hazing conduct cases in recent years, and other groups with established partnerships are areas to consider when rolling out educational requirements. Priority areas include student organizations, SFL, club sports, and honor societies. Other priority areas can be more difficult to determine. There are also university academic courses that operate like a student organization, such as marching bands, performing arts groups, academically based curricular experiences, and Reserve Officers’ Training Course (ROTC). Athletics does not operate as an academic program or student organization, yet is another important partner to consider. They have their own compliance requirements from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) that need integrating with legal requirements. It is encouraged that practitioners engaged in anti-hazing policy and practice implementation create a comprehensive list of priority areas and ensure stakeholders review the list against the requirements of the law.

- Leveraging Partnerships: If professionals can ever attend the Interdisciplinary Hazing Prevention Institute[4], they should. Faculty in the program discuss the importance of partnership in prevention work. Participants are coached to identify partners and classify their degree of collaboration. All partners have roles, but not everyone needs to be in the weekly working group. Correctly identifying partnerships make efforts more effective and efficient. First, there are partners doing most of the heavy lifting, writing curriculum, creating policy, and overall implementation of objectives. Allies might help with the grunt work but can also provide connection to others needed at the table. Lastly, champions are the folks who might have a high-level decision-making role or have influence and access to key stakeholders and larger communities. Utilizing these three types of partnership has proven helpful in creating buy-in and starting the first steps of social norming. Partnerships can be from the priority areas identified previously in addition to relevant functional areas such as student conduct, legal council, government affairs, university and local law enforcement, human resources, Title IX, and health promotion offices. When beginning to collaborate with these areas, be mindful of terminology and acronyms. There will be many knowledge gaps, and every priority area will refer to the joining process as something different.

- Building a Team: To implement legislation and create change, campuses should consider creating hazing prevention working groups. The Ohio Statewide Education Plan[5] suggested that “a coordinated team of individuals should oversee efforts to implement the anti-hazing framework, training and education programs, and assessment tools” (p. 37). Thinking innovatively and broadly about the makeup of working groups will assist in the long-term success of accomplishing directives. Successful working groups should include staff representatives from the identified priority areas. Additionally, student representatives must have space to engage in the working groups.

It is suggested a senior leader deliver the appointment and charge the working group. This communicates that hazing prevention is a commitment of the institution and a community-wide initiative. Working group structures will vary depending on a campus’s cultures and needs. It is imperative that prevention groups listen, learn, and observe to promote adaptability and meet the developmental needs of various student groups. One of the first hazing prevention working group charges is understanding the institution’s current climate. This includes assessing the organization’s commitment to anti-hazing initiatives. There are several available tools and resources to aid in assessment. The Hazing Prevention Toolkit[6] is one of many resources that can assist practitioners. Once awareness and acknowledgment occur, the working group can set goals and take action steps to implement legislation and enact change.The final step is categorizing the goals and action items of the working group into three subsections: reporting, training, and policy. The reporting subsection of the group should prioritize the evaluation and adaptation of reporting structures and forms and the development of a marketing campaign regarding reporting. The education subgroup is responsible for curriculum development regarding anti-hazing strategies, information, and overall compliance training. They should determine education delivery methods to reach various audiences. Lastly, the policy group is charged with editing the university’s hazing policy. They need to ensure the policy aligns with the law and requirements of state departments of higher education.

It is suggested a senior leader deliver the appointment and charge the working group. This communicates that hazing prevention is a commitment of the institution and a community-wide initiative. Working group structures will vary depending on a campus’s cultures and needs. It is imperative that prevention groups listen, learn, and observe to promote adaptability and meet the developmental needs of various student groups. One of the first hazing prevention working group charges is understanding the institution’s current climate. This includes assessing the organization’s commitment to anti-hazing initiatives. There are several available tools and resources to aid in assessment. The Hazing Prevention Toolkit[6] is one of many resources that can assist practitioners. Once awareness and acknowledgment occur, the working group can set goals and take action steps to implement legislation and enact change.The final step is categorizing the goals and action items of the working group into three subsections: reporting, training, and policy. The reporting subsection of the group should prioritize the evaluation and adaptation of reporting structures and forms and the development of a marketing campaign regarding reporting. The education subgroup is responsible for curriculum development regarding anti-hazing strategies, information, and overall compliance training. They should determine education delivery methods to reach various audiences. Lastly, the policy group is charged with editing the university’s hazing policy. They need to ensure the policy aligns with the law and requirements of state departments of higher education. - Education: When there are new policies and procedures, pre-existing initiatives need to be examined to understand how they can support anti-hazing strategies. First, training and education will be the main focus of the implementation phase. It is critical to determine what the learning outcomes are for each of the required training sessions, as well as which interventions are best suited to which specific audiences. For example, many laws require all university faculty, staff, and volunteers to report to law enforcement and receive training regarding this requirement. This means considering the learning styles and needs of a wide range of learners.Next, the anti-hazing language used in the training should complement existing messaging and efforts. Commonly understood language and tools utilized across the campus should be considered. Examining language used in Title IX and bystander training initiatives will not only aid in designing anti-hazing education, but communities will be able to further build on skills they have already learned and apply them in a group context. Furthermore, if the university chooses to purchase or develop an online module for education, ensuring module customization to address university specifics is critical. Customization should include university policies, resources, and reporting processes. Additionally, if the university has branch campuses, care should be taken to ensure education and any customizations are inclusive of these entities, especially when it comes to reporting to local law enforcement. Lastly, considerations need to be made to provide required training to non-university community members. Populations affected by this could be non-faculty/staff advisors, volunteer coaches, and students joining city-wide chapters from other universities.

As Ohio’s SFL professionals reflect back and engage with colleagues across the state, it should be noted there was not a cookie-cutter approach to anti-hazing work. It is important to understand specific campus culture, organizational structures, stakeholders, and available resources. It takes a higher education village to be effective in implementing anti-hazing legislation. Therefore, as an SFL practitioner, do not try to tackle anti-hazing and prevention work alone. Below is a list of additional recommendations for practitioners tasked with implementing new anti-hazing policies, laws, or practices:

Recommendations

- Find your village

- Maximize university resources and knowledgeable faculty/staff.

- Be strategic in involving students. Student involvement can bring insight to a group and empower others to be change agents in the campus community.

- Build a relationship with legal counsel and government affairs staff. They can be great allies and partners in interpreting laws and how to apply strategies within your university purview.

- Build a community with professionals in your state.

- Establish a relationship with the university marketing department and determine how they can assist with the dissemination of information and social norming campaigns and public relations.

- Define roles

- Determine who the senior leader will be to lead the charge.

- Determine early on what SFL staff’s role is with these efforts. If the department is leading, hazing prevention efforts may be perceived as applying exclusively to SFL.

- Set job descriptions or specific tasks for prevention group team members and partners who are engaging in prevention work.

- Universities will need to determine who is responsible for compliance expectations. This includes tracking training completion and creating a semesterly public violation report.

- Evolving and innovating

- Try new prevention initiatives while still being intentional about programming, time, and resources.

- Create a plan to communicate the university’s updated anti-hazing policies and procedures to national volunteers, headquarters, and housing partners.

- Map out what efforts are meeting compliance standards and what practices are beyond compliance.

- Take this opportunity to talk about how to prevent hazing and build healthy group dynamics in the joining process.

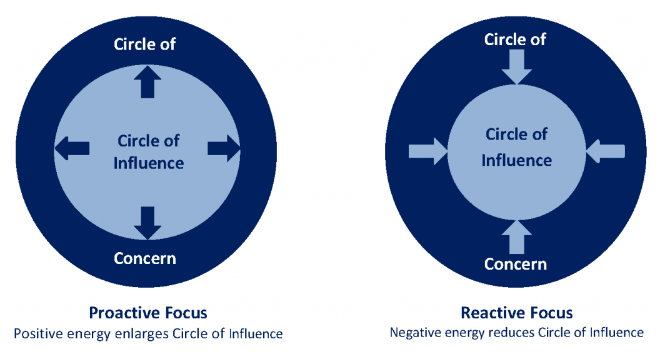

- Practitioners and work groups should employ Stephen Covey’s circle of concern, influence, and control concepts.

- Create an intentional assessment plan to evaluate learning outcomes, satisfaction, and compliance efforts annually.

[1] https://www.nohaze.org/

[2] https://www.antihazingcoalition.org/

[3] https://iuc-ohio.org/presidents-council/

[4] https://hazingprevention.institute/

[5] https://highered.ohio.gov/initiatives/campus-initiatives/hazing-prevention/hazing

[6] https://stophazing.org/

References

Allan, E. J., Payne, J. M., & Kerschner, D. (2018). Transforming the culture of hazing: A research-based hazing prevention framework. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 55(4), 412-425.

Tylock, A. (2021). A 50-state summary of hazing laws. SUNY Student conduct institute. A-50-State-Summary-of-Hazing-Laws.pdf (suny.edu)

About the authors

Stacey Allan (She/Her) earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in theatre from Lake Erie College and a Master of Science in Education degree with a focus in student affairs and leadership practices from Youngstown State University. Currently, Stacey serves as the Associate Director of Student Engagement at Bowling Green State University (BGSU). Before she arrived at BGSU, she worked as the Director of Student Involvement at Muskingum University. Her prior higher education professional experiences include the experiences in fraternity and sorority life, student involvement, residence life, student conduct, civic engagement, and leadership development. Stacey has served as a member of the professional development committee with AFA since 2020. She is a member of Gamma Phi Beta and currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Higher Education Administration.

Stacey Allan (She/Her) earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in theatre from Lake Erie College and a Master of Science in Education degree with a focus in student affairs and leadership practices from Youngstown State University. Currently, Stacey serves as the Associate Director of Student Engagement at Bowling Green State University (BGSU). Before she arrived at BGSU, she worked as the Director of Student Involvement at Muskingum University. Her prior higher education professional experiences include the experiences in fraternity and sorority life, student involvement, residence life, student conduct, civic engagement, and leadership development. Stacey has served as a member of the professional development committee with AFA since 2020. She is a member of Gamma Phi Beta and currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Higher Education Administration.

Will Cangialosi (He/Him) currently serves as the Assistant Director for Chapter Services in the Department of Sorority and Fraternity Life at The Ohio State University. In this role, he has worked on leadership development and prevention initiatives. Will additionally served as the Interim Hazing Prevention Specialist and lead the Collin’s Law training workgroup at Ohio State in 2022. Will is a two-time alumni of SUNY Plattsburgh, where he became a member of Alpha Sigma Phi and received his Bachelor’s in Chemistry and his Master’s in Student Affairs and Higher Education and Counseling. Will is a national safe team volunteer for Sigma Sigma Sigma Sorority and has served on the AFA Annual Meeting Graduate Student Experience Committee since 2018.

Will Cangialosi (He/Him) currently serves as the Assistant Director for Chapter Services in the Department of Sorority and Fraternity Life at The Ohio State University. In this role, he has worked on leadership development and prevention initiatives. Will additionally served as the Interim Hazing Prevention Specialist and lead the Collin’s Law training workgroup at Ohio State in 2022. Will is a two-time alumni of SUNY Plattsburgh, where he became a member of Alpha Sigma Phi and received his Bachelor’s in Chemistry and his Master’s in Student Affairs and Higher Education and Counseling. Will is a national safe team volunteer for Sigma Sigma Sigma Sorority and has served on the AFA Annual Meeting Graduate Student Experience Committee since 2018.